Robert Habeck’s trip to Qatar and the United Arab Emirates was aimed at finding new sources of natural gas. Germany obtains 55 percent of its natural gas from Russia, but with the war of aggression against Ukraine initiated by Russia, this should come from other sources as quickly as possible. Actually, green hydrogen from renewable sources should take over this task. However, the market ramp-up is still in its infancy. The urgency of the situation is shown by the fact that a green minister of economics is trying to find fossil raw materials in the Arab world. Neither country is considered a model of democracy, and it is also a question of exchanging authoritarian states as energy suppliers. The shock and bewilderment caused by the news from Ukraine is still deep-seated.

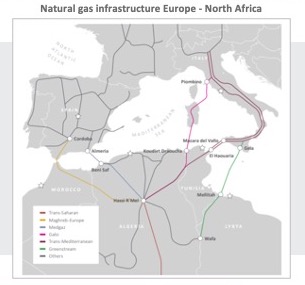

Alternative sources of natural gas can also be found in Africa. There is also a pipeline network under the Mediterranean that can transport natural gas to Europe. Geostrategically, therefore, the conditions are optimal. Algeria is the tenth-largest gas producer in the world and supplies its liquefied natural gas (LNG) on a large scale to the European market. The North African country is considered one of the richest economies in Africa because of its export of fossil raw materials. Export revenues from the fossil commodities business contribute 27 percent to the gross domestic product. In recent years, natural gas production in Algeria has been only moderate. The gas fields are increasingly exhausted. So far, the main consumers of the gas are Italy and Spain. Algeria is also not considered a model country for democracy and is undergoing a difficult democratisation process.

Egypt does not have to complain about a lack of natural resources. By far the most important natural resources in Egypt are oil and natural gas. Most of the oil is exported. The daily production volume corresponds to about 10 percent of Saudi Arabia’s production. The natural gas is used to produce electricity in the country and is exported to industry and private households. About 7.8 billion cubic metres are produced per year. Gas fields have been discovered in the recent past. The Zohr field is located off the coast in the Mediterranean Sea. With an estimated capacity of 30 million cubic metres, it is the largest field in the Mediterranean to date. The production of natural gas, also for export, is a mainstay of the economy. For the nearby export markets, these gas sources are an alternative to Russian gas. This became apparent during the Ukraine crisis. Egypt is very interested in marketing this natural gas. In addition, it wants to produce green hydrogen because of its cheap resources. This, too, is intended for export in addition to its own needs.

Another option is the West African country of Nigeria. Nigeria, Niger and Algeria have agreed on the construction of a trans-Saharan gas pipeline more than 4000 kilometres long and costing billions. According to media reports, once completed, the pipeline will transport up to 30 million cubic metres of gas per year to Algeria, where it can be connected to the existing network in Algeria to Europe.

Stefan Liebiung, Chairman of the Africa Association of German Business, comments: “At the same time, Europe could thus provide economic support to African countries that have been hit hard by the consequences of the war in Ukraine. Egypt, for example, is one of the largest wheat importers in the world and depends on supplies from Ukraine to feed its population. Europe could at least cushion the economic consequences of the war for Africa a little by buying gas,” Liebing suggests.

In the long term, countries like Ghana, Libya, Mozambique, Senegal and Tanzania could also supply Europe with liquefied natural gas if the corresponding infrastructure on both sides of the Mediterranean were upgraded. This could then be used to transport green hydrogen from Africa to Europe. Africa offers even greater opportunities for this. Germany and the EU must therefore finally do their homework. Otherwise, we will remain vulnerable to supply crises, and Europeans will be unable to benefit from either natural gas or hydrogen from Africa,” concludes Stefan Liebing.

Where is the green hydrogen? First of all, Thyssen Krupp, for example, needs 700,000 tonnes for its steel production alone. To produce them in Africa, for example, is a huge task. Billions of dollars of investment have to be made. Moreover, many people in Africa have no access to electricity. Also, renewable energy pioneers like Morocco are emitting more and more carbon dioxide. The population is growing and needs more energy. Financing and business cases have to be designed for this. Then there is the development of a transport infrastructure. Green hydrogen is difficult to transport by ship. It can be converted into ammonia NH3 and split again into the elements nitrogen N2 and hydrogen H2. Ammonia transport is state of the art. However, the conversion process costs energy and money. For the market ramp-up, there is a paradigm shift in Germany after the change of government. While Altmeier (CDU) relied on the market, Habeck (Greens) is working more with subsidies. The new federal government has therefore launched the H2 Global project. It has a volume of 900 million. There is also an H2-Global foundation.

The activities of the H2-Global Foundation are part of my arctical reporting.

background in the book I am currently writing with Paul van Son (President of Dii Desertenergy): Large-scale Renewable Projects

Author: Dr. Thomas Isenburg